At CPS high schools, a stark racial divide on when cops are called on students and arrests

For years, Black students and activists have complained about having police in their schools, saying it results in staff targeting Black youth. CPS

Posted on January 18, 2021

For years, Black students and community activists have complained about having uniformed police officers in their schools, saying the result is that school staff members target Black children, getting cops involved over routine disagreements, which leads to officers escalating those situations and criminalizing Black teenage behavior. They also say the police don’t know how to handle the needs of students in special education and shouldn’t be the ones to respond to a student in crisis.

For years, Black students and community activists have complained about having uniformed police officers in their schools, saying the result is that school staff members target Black children, getting cops involved over routine disagreements, which leads to officers escalating those situations and criminalizing Black teenage behavior. They also say the police don’t know how to handle the needs of students in special education and shouldn’t be the ones to respond to a student in crisis.

The school system’s own data backs that up, according to a Chicago Sun-Times analysis of Chicago Public Schools (CPS) records that finds a stark divide in how Black students and those in special education are treated compared to other students. Among the Sun-Times’ findings:

- Students who attend a high school that has a Chicago police officer stationed inside are four times more likely to have the police called on them than kids at high schools that don’t have in-house cops.

- Students at majority-Black high schools are almost three times more likely to have the police called on them than kids at schools with a student population that’s more heavily white than the citywide average.

- Black girls face some type of intervention by school police officers at a rate eight times higher than white girls and nearly 14 times higher than Asian American girls.

- Cops are called on children in special education more than three times more often than other students.

- At high schools with police officers inside, cops intervene more frequently at schools with majority-Black student populations than those where Black students are a minority.

- And student arrest data released for the first time by CPS this past week shows those police notifications have led to arrests of Black students at a rate 91⁄2 times higher than white students, six times higher than Latino students and 38 times higher than Asian American students. Of 11,527 student arrests made in Chicago over the past nine school years — including the shortened 2019-2020 year — 9,001 have been Black students. That’s 78.1%. That’s even though Black students have accounted for 39% of CPS’ enrollment during that time, records show.

The “appalling” data at CPS largely mirrors the disparate rates of policing in schools nationally, says Pauline Lipman, an education policy studies professor and researcher at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

CHICAGO SUN TIMES DIGITAL SUBSCRIPTON AVAILABLE HERE

“All the research pretty much shows the same thing: Police in schools actually don’t keep students safe,” says Lipman, who has studied CPS policies for over two decades. “Police in schools make Black and Brown students in particular more fearful of going to school. It affects their educational experience and can begin to set them on a path in which various institutions criminalize them. This is an extremely serious finding and one that should be a very strong argument, particularly in this moment of national reckoning, for removing police from schools.”

Mayor Lori Lightfoot and CPS leadership have declined to issue a blanket removal of cops from schools even as they face public scrutiny that’s only gotten stronger since the Chicago Board of Education approved a $33 million contract last August with the Chicago Police Department and again this summer as the nation has grappled with the history of racism in America and the role of police in Black communities and schools.

Jadine Chou, CPS’ safety and security chief, says the school system has been working to eliminate school-policing disparities, particularly for Black students.

“Nothing is more important to all of us here at CPS than ensuring all of our students are treated fairly and have equitable access to our schools,” Chou says.

Lightfoot and CPS have proposed reforms to what they call the School Resource Officer, or SRO, program.

On Wednesday, CPS officials will present a revised, $15 million agreement to the school board for approval. The board, which decided in June not to terminate its relationship with the police department, faces another key vote in which it could elect not to renew the police contract that’s set to expire at the end of this month.

The majority of calls during the 2018-19 year — 1,054 — were concentrated at 94 high schools serving a total of 76,791 students.

The police got involved with students in preschool through second grade 26 times.

Third- through fifth-graders were the subject of 95 police calls.

And 572 notifications were for sixth- through eighth-graders.

Altogether, officers were called 1.37 times per 100 students in the 2018-19 school year.

The racial disparities become clear when race and school participation in the SRO program are taken into account.

At 70 non-charter high schools that have officers in their building, 1.52 police notifications were made per 100 students — a total of 1,014. For the 23 high schools without in-house officers, it was 0.39 calls per 100 children — 40 total notifications.

Of the 15 schools in the SRO program with the highest rates of police calls, 10 were majority-Black schools. Of the 15 schools with officers that had the lowest notification rates, 11 were majority non-Black.

7th-, 8th-graders’ argument criminalized

McFarland, now 18, graduated in June from Austin College and Career Academy High School, which in recent weeks decided to keep officers in its building. McFarland says when he was an eighth-grader at Sumner Elementary School, a group of boys got into an argument with him and his friends. Security guards and teachers at the school stepped in, then one of the adults called the police. The officers detained all of the boys, who were in seventh and eighth grades.

McFarland says the situation could have been handled very differently, without elementary students being made to feel like criminals over an argument, if the school had social workers and counselors to talk them through their struggles.

“The kids that actually started saying stuff to us and tried to get into it with us, I feel like maybe they didn’t have anybody to talk to,” he says. “Maybe something was going on at their house that nobody ever knew about. The only reaction that they know is violence.

“If we, as a community, as schools, as human beings, if we just have the proper resources and the right education and the right people to teach us, we wouldn’t have these situations. Every time the word Black comes into a sentence, police come into it.”

He says school and governmental leaders need to understand the degree to which Black people fear the police and how students carry those feelings with them every day.

“If I see officers running toward me, the first thing that I think is I’m gonna die,” McFarland says. “I fear for my mom. I know how big of an impact it’s gonna be on her if she loses one of her sons. It makes you feel that you don’t have a place in this world.”

Lipman, the UIC professor, says Black and Latino students face hostile policing in the streets, and “when they go to school, they see the same police in a school that’s supposed to be a supportive and caring and nurturing learning environment. That only magnifies the trauma that they’re already experiencing in the community.”

Latino students don’t face the same rates of police notifications at CPS schools as Black students, but they are still a little more than 21⁄2 times more heavily policed than white students, records show.

Schurz High School had most police calls

A predominantly Latino school, Schurz High School in Irving Park on the Northwest Side, logged the most calls to police in the 2018-19 year. Officers intervened with students at Schurz 229 times that year.

The next -closest was Taft High School, which had more than twice the number of students enrolled. Taft had 75 notifications, about three times fewer.

Even taking into account that it has 1,600 students — making it CPS’ 11th-largest school — Schurz calls the cops at the third-highest rate in the city, with 14.65 calls per 100 students.

Other schools with high rates of notifications were Tilden High School, with 21.3 calls per 100 students, and Marshall High School, with 10.6 calls per 100 students.

The Local School Councils at Schurz, Taft, Tilden and Marshall all voted earlier this month to keep their police officers.

Even when the presence of in-house officers is removed from the equation, a disparity still exists between majority-Black schools and those with more white students than the citywide average of 10.8%. No CPS high schools are majority-white.

At CPS’ 37 majority-Black high schools in 2018-19, 1.66 police calls were made per 100 students. At the 18 schools that were more heavily white than average, there were 0.62 notifications per 100 kids — a rate almost three times lower.

That amounts to about half as many total police notifications at the whiter-than-average schools than the majority-Black schools — 168 vs. 313 — despite the whiter schools serving 8,500 more students — 27,063 vs. 18,537.

Overall, 58.8% of police calls that year involved Black students, who now make up 35.9% of CPS’ enrollment.

Black girls face one notification per 100 students — eight times the rate of white girls, 14 times more than Asian American girls and about 21⁄2 times more than Latina girls.

Aja Reynolds, a visiting assistant professor of urban education and race studies at Wayne State University in Detroit, says Black girls routinely are seen as troublemakers because they don’t conform to the idealized version of white girlhood or womanhood. That leads to higher rates of police intervention.

“Oftentimes, they’re kicked out of class or they’re in trouble because they may talk back,” says Reynolds, a former Chicago community organizer working with Black girls on the South Side. “And their talk-back may be them advocating for themselves. But because it comes through a Black girl’s body, it’s seen as talking back.

“The basis of how we understand womanhood, who represents that, who represents femininity, is really boxed into this cisgender, white, middle-class woman,” Reynolds says. “And then Black girls and women aren’t often seen in that same way.”

Perez, an incoming senior at Lindblom Math and Science Academy, was in special education at her elementary school when an officer pulled her out of a classroom for having headphones on.

“I remember it so vividly because I was screaming, ‘Stop,’” Perez says. “I didn’t understand. It was no warning. I hadn’t fought anybody, I hadn’t did anything. I was literally sitting in class. I’m just scared at this point. It was a hard year for me, it was a lot going on. I remember being in this situation, and it was, like, what was solved? For what?

“My school wasn’t heavily policed, yet I still had an experience like that,” she says. “And that was a light experience compared to a lot of other young Black women who have been in CPS and have had much worse experiences.”

Jackson and Bell say they feel they have targets on their backs at school because of their Black skin.

A steady drop in police calls

Chou, CPS’ safety and security chief, points to policies put in place last fall that limit the circumstance under which officers can be called to interact with students, prohibiting police involvement in school discipline, as a way the school system is trying to change the system of policing in schools.

The reduction in police calls has been steady in Chou’s nearly nine years on the job. Chou attributes those reductions to the introduction of training and the elimination of a zero-tolerance policy.

“We’re training staff to understand how to approach situations with a trauma-informed lens,” she says. “We’re training staff on implicit racial bias to understand what we, as adults, need to do to eliminate those shortcuts that sometimes people take in making assumptions and how we react to a situation.

“We’ve made tremendous progress. Our goal is to eliminate the school-to-prison pipeline. We’re on this journey, and we’re committed to making sure that happens.”

At the mayor’s direction, the Local School Councils at about 70 high schools have considered whether to keep officers in schools. Fifty-four schools decided to keep their cops for the upcoming school year, and 17 have removed them.

Officials at some schools have said their officers are friendly and keep students safe from outside trouble. Others have said they’ve been forced to choose between an officer or nothing, complaining about CPS’ stance that schools that give up their SROs can’t use that money for anything else.

Schools with fewer Black students generally were the ones to kick out the police. Nearly all majority-Black high schools chose to keep them. That leaves most majority non-Black schools without cops and all but two majority-Black CPS high schools with officers in the building.

Nader Issa, Education reporter. Nader Issa covers education for the Chicago Sun-Times

SEE ALSO:

More Race Relations Articles

Sexual Bias Articles

Mental Health Articles

How Drugs and Alcohol Affect the Brain and Body

WA. Counselor Directory: find a therapist near you

How helpful is this web page to you?

(and how can we can improve this page for you?)

not helpful

very helpful

Other Articles

Confessions of a white baby boomer on race relations

Opinion: June 12, 2020 “Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy were my heroes growing up in New York in the 1960s. My parents had taught me and my brother to embrace racial justice and tr... read more

How history has led to an extraordinary moment

Aaron Dixon has seen a lot in his 71 years. The leader of Seattle’s Black Panther Party in the height of the turbulent 1960s, Dixon lived through the uprisings after the murder of the Rev. Dr. Martin L... read more

I do not want any help from your kind

Being a doctor while Black

Throughout my medical training, there were situations of patient’s refusing treatment based on the color of my skin, even in emergencies. One night, in Charlottesville, Virginia, the buzzing of the... read more

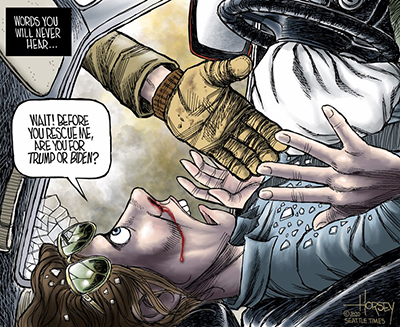

What will come of the wreckage of a divided America?

It's in our hands

Several weeks ago, I found myself straddling the centerline of a rural highway, kneeling on hot asphalt, aiming a charged fire hose at the aftermath of a head-on collision. Neither car was yet burning, but f... read more